The Silk Road: How Ancient Trade Routes Shaped the Modern World

The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road: Connecting East and West Through Ancient Trade Routes

The Silk Road: Connecting Ancient Civilizations

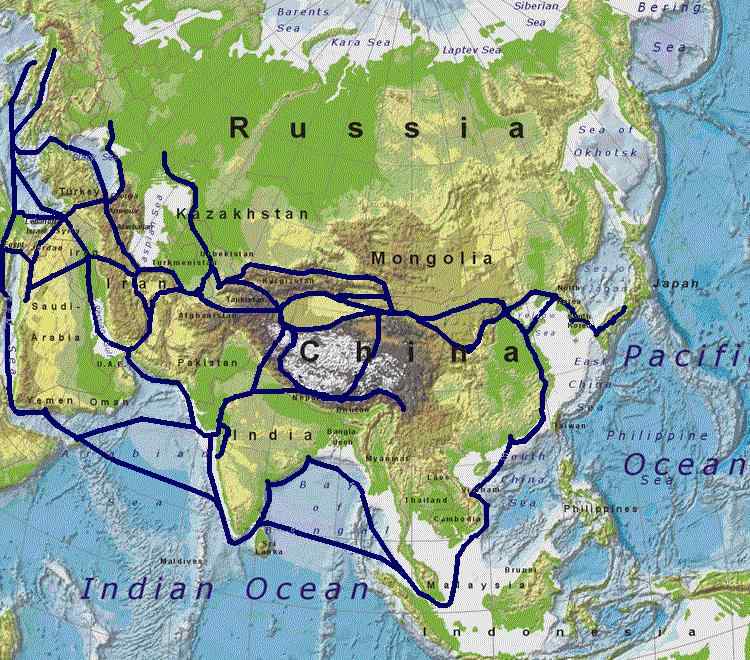

Imagine a sprawling network of ancient trade routes that fundamentally reshaped human civilization for over two millennia. This was the Silk Road, not a single path, but a vast, interconnected web spanning more than 4,000 miles, linking the diverse cultures of the East and West. Far more than just a conduit for silk—its most famous commodity—it served as a dynamic corridor for the exchange of goods, ideas, religions, and technologies, profoundly impacting the civilizations it touched. This article delves into the Silk Road’s intriguing origins, its vast economic and cultural influence, the reasons behind its gradual decline, and its remarkable modern revival through initiatives like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Silk Road's Genesis: From Han Dynasty Trade to Mongol Expansion

The foundations of the Silk Road were established during China’s powerful Han Dynasty (207 BCE – 220 CE). Emperor Wu initiated these ancient trade routes by dispatching the diplomat Zhang Qian on a critical mission to form alliances against the Xiongnu, a formidable nomadic confederation threatening China's northern borders. Although Zhang Qian’s primary diplomatic goals were only partially met, his expeditions between 138–126 BCE successfully opened up vital trade routes into Central Asia. This marked the beginning of significant exchanges, particularly Chinese silk and jade for Central Asian horses—an essential resource for China’s developing cavalry.

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the Silk Road truly flourished under a stable and globally connected empire. Chang’an (modern Xi’an), the Tang capital, emerged as a vibrant, multicultural center where merchants, scholars, and diplomats from Persia, India, and the Mediterranean converged. Trade expanded dramatically, moving beyond land routes to include extensive maritime Silk Roads. These sea lanes linked China to Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa, facilitating the transport of valuable commodities like spices, ceramics, and textiles.

Later, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368) played a crucial role in revitalizing these ancient trade routes by establishing the Pax Mongolica. This period of relative stability and secure passage under Genghis Khan and his successors led to a significant increase in the movement of goods, diplomatic envoys, and travelers. Notable figures like Marco Polo embarked on their journeys during this era, with their detailed accounts introducing Europeans to the immense wealth and advancements of the East.

Beyond Silk: A Global Exchange of Goods, Ideas, and Technologies

While silk remained the quintessential export from China, the Silk Road facilitated a far more expansive and diverse array of commodities, driving a truly global exchange:

From the East: This included highly sought-after goods such as tea, porcelain, paper, gunpowder, iron, and crucial agricultural innovations like citrus fruits and advanced rice cultivation techniques.

From the West: Merchants brought wool, linen, precious gold and silver, exquisite glassware, as well as new crops like grapes, walnuts, and alfalfa (which significantly transformed Chinese agriculture). Horses and camels, vital for transport across the vast routes, were also key exchanges.

From Central and South Asia: This region contributed valuable spices (including pepper, cinnamon, and ginger), precious stones (such as lapis lazuli and turquoise), and fine textiles like cotton and intricately woven carpets.

Beyond luxury goods and raw materials, the Silk Road served as an indispensable conduit for technological transfer that reshaped the world:

The revolutionary invention of papermaking in China spread westward, fundamentally changing record-keeping and scholarship in the Islamic world and later in Europe.

Groundbreaking innovations like gunpowder and compass technology traveled from China to the Middle East and Europe, profoundly altering the nature of warfare and maritime navigation.

Advanced mathematical and astronomical knowledge, including the ingenious Indian numeral system (which later became known as Arabic numerals), reached the Western world through the dedicated work of Persian and Arab scholars.

Cultural and Religious Diffusion: The Silk Road's Impact on Civilizations

As a vibrant crossroads of civilizations, the Silk Road became a fertile ground for the diffusion of religions and philosophies:

Buddhism, originating in India, spread extensively eastward via Central Asia, leaving an indelible mark on China, Korea, and Japan. Iconic sites like the Dunhuang Caves and Yungang Grottoes stand as powerful testaments to this syncretism, showcasing a remarkable blend of Indian, Greek, and Chinese artistic styles.

Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism also reached China by the 7th century, with historical records detailing Nestorian communities in Tang-era Xi’an.

Islam expanded eastward after the 8th century, primarily through the journeys of Persian and Arab merchants. This led to the establishment of thriving Muslim communities across China, including the notable Hui people.

Zoroastrianism and Judaism also found significant footholds along the route, with Jewish traders settling in Kaifeng by the Song Dynasty.

Beyond religious doctrines, artistic and intellectual exchanges were equally transformative and widespread:

Greek and Persian motifs profoundly influenced Buddhist art in Central Asia, giving rise to unique styles like the Gandhara style.

Exquisite Chinese ceramics and lacquerware were highly prized and sought after throughout the Middle East and Europe, demonstrating the artistic influence of the East.

Crucial medical knowledge, encompassing both Ayurvedic and Greek humoral theories, spread widely across Eurasia, contributing to advancements in global healthcare practices.

Decline of the Silk Road: The Shift to Maritime Trade

The prominence of the Silk Road experienced a gradual yet multifaceted decline due to several key factors:

1. Political Fragmentation: The collapse of the vast Mongol Empire in the 14th century shattered the Pax Mongolica, severely disrupting the security and stability of overland trade. This fragmentation made travel much riskier and less reliable.

2. Rise of Maritime Trade: European powers, particularly Portugal and Spain, became intensely driven to find direct sea routes to Asia. This quest intensified after the Ottoman Empire’s control of the Levant made traditional overland trade increasingly costly and difficult. Vasco da Gama’s 1498 voyage around Africa to India was a monumental turning point, establishing a viable alternative.

3. Economic Shifts: The devastating Black Death (1347–1351), which tragically spread via Silk Road caravans, decimated populations across Eurasia. This catastrophic demographic collapse severely disrupted established trade networks and reduced demand for many goods.

4. Technological Advances: Significant improvements in shipbuilding and navigation technology made maritime trade far more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective than the arduous and time-consuming journeys undertaken by camel caravans.

By the 16th century, the Silk Road had largely lost its dominant status as a global trade artery, though regional trade continued to persist within Central Asia.

The Modern Silk Road: China’s Ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

In 2013, China unveiled the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious $1 trillion infrastructure project designed to revive global connectivity reminiscent of the ancient Silk Road. This modern initiative aims to foster unprecedented economic integration through:

Extensive land corridors (e.g., the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the New Eurasian Land Bridge).

Strategic maritime routes connecting Chinese ports to vital regions in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Advanced digital and energy networks, including the rapid expansion of 5G technology and critical oil/gas pipelines.

While the BRI promises significant economic integration and development for participating nations, it has also encountered considerable criticism concerning:

Accusations of debt-trap diplomacy (a prominent example being Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port).

Escalating geopolitical tensions, particularly with the U.S. and India, due to its strategic implications.

Serious environmental concerns stemming from the large-scale nature of its infrastructure projects.

Despite these controversies, the BRI unequivocally reflects the Silk Road’s enduring legacy—a powerful symbol of connecting economies and cultures on a global scale.

The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road

The Silk Road was far more than a mere trade network; it represented the world’s first truly globalized system, fostering unparalleled cultural, religious, and technological exchanges between diverse civilizations. Its eventual decline did not erase its profound impact; instead, it meticulously laid the groundwork for the modern era of globalization we experience today. Initiatives like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) vividly echo its original spirit, serving as a testament to the fact that the Silk Road’s legacy persists as a powerful symbol of interconnectedness, innovation, and vital cross-cultural dialogue. Whether through ancient camel caravans or modern high-speed railways, the timeless quest to bridge East and West remains as crucial and transformative as ever.