The Silk Road: How Ancient Trade Routes Shaped the World and China’s Modern Revival Efforts

The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road: Connecting Ancient Worlds and Modern Trade

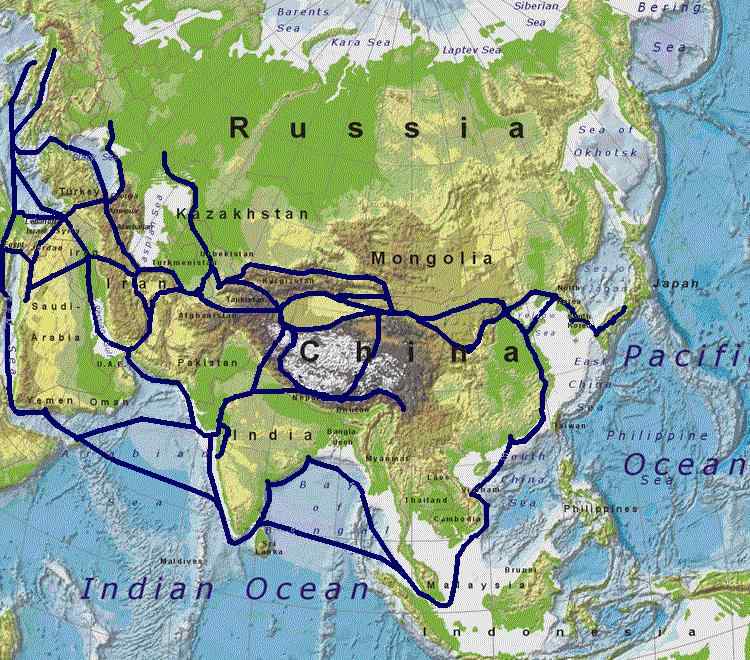

Introduction: Embark on a captivating journey through history to explore the legendary Silk Road. For over two millennia, this wasn't just a single route, but a vast, interconnected network of trade paths stretching more than 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles). It seamlessly linked East Asia, particularly China, with the Mediterranean, South Asia, and even Sub-Saharan Africa. Far more than a conduit for its namesake commodity, silk, the Silk Road served as a dynamic channel for the exchange of goods, groundbreaking technologies, diverse religions, and transformative ideas, profoundly shaping the civilizations it touched. This article delves into the Silk Road’s origins, its immense economic and cultural impact, the reasons for its eventual decline, and its ambitious modern revival through China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Origins and Development of the Silk Road: From the Han Dynasty to the Mongol Empire

The Silk Road's rich history began with its foundations laid during China's Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Emperor Wu played a pivotal role by sending the diplomat Zhang Qian on missions to forge alliances against the Xiongnu, a nomadic threat to China's northern frontiers. Although Zhang Qian's military goals weren't fully met, his expeditions (138–126 BCE) successfully established vital diplomatic and trade connections with Central Asia. This opened the door for the exchange of valuable Chinese silk, jade, and lacquerware for commodities like horses, grapes, and woolen goods.

Early trade along the Silk Road often depended on nomadic intermediaries and was challenging, marked by banditry and harsh environments. Yet, the network saw significant expansion under the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), a golden era for Chinese trade and cultural diffusion. The Tang government strengthened trade by standardizing weights and measures, establishing military garrisons along crucial routes, and fostering vibrant cosmopolitan urban centers. Cities such as Chang’an (modern Xi’an) and Dunhuang transformed into bustling hubs for merchants, scholars, and missionaries.

Later, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), led by figures like Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan, further secured the Silk Road. By uniting much of Eurasia under a single political system, the Pax Mongolica era ensured safer passage for traders, including the famous Marco Polo, whose detailed accounts introduced Europeans to the vast wealth and advanced cultures of the East.

Key Commodities and Trade Dynamics of the Silk Road: Beyond Just Silk

While silk was undeniably the most renowned export from China, the Silk Road was crucial for transporting an incredibly diverse array of goods. These commodities fundamentally reshaped economies and everyday life across entire continents:

From East Asia (especially China):

- Silk (highly valued in Rome, often worth its weight in gold)

- Porcelain (a craft later imitated in Persia and Europe)

- Tea (introduced to Central Asia and subsequently to Europe)

- Paper and gunpowder (revolutionary technologies for warfare and communication originating in China)

- Spices (including cinnamon, ginger, and later pepper from Southeast Asia)

From Central Asia and the Middle East:

- Horses (critically important for Chinese cavalry)

- Wool, carpets, and textiles (from regions like Persia and the Central Asian steppes)

- Lapis lazuli, turquoise, and jade (prized materials for jewelry and art)

- Glassware and metalwork (from the sophisticated Roman and Byzantine Empires)

From South Asia and Beyond:

- Cotton, indigo, and sugar (crops later cultivated in the Mediterranean region)

- Precious stones (such as diamonds, rubies, and sapphires from India and Sri Lanka)

- Slaves and exotic animals (including lions and cheetahs for royal courts)

The Silk Road's trade was never just one-sided. Central Asian cities, including Samarkand, Bukhara, and Kashgar, served as vibrant cultural and economic crossroads. Here, goods were not only exchanged but also taxed, and new ideas readily spread. This ancient trade network also played a key role in the distribution of essential commodities like salt, grains, and metals, which were vital for sustaining local economies.

Cultural and Religious Exchange Along the Silk Road: A Highway for Ideas

Beyond mere commercial transactions, the Silk Road truly functioned as a highway for intellectual and spiritual exchange, profoundly reshaping religions, scientific understanding, and artistic expressions across Eurasia throughout its history:

Religious Diffusion across the Silk Road:

- Buddhism traveled from India into China (through key stops like Khotan and Dunhuang), subsequently influencing Korea and Japan. The iconic Mogao Caves near Dunhuang remain a testament, preserving countless Buddhist murals and scriptures from this period.

- Nestorian Christianity made its way to China by the 7th century, with the Daqin Pagoda in Xi’an standing as evidence of its presence.

- Manichaeism (a dualistic faith originating from Persia) and Zoroastrianism also gained followers across Central Asia and China.

- Islam expanded eastward after the 8th century, largely propelled by Persian and Turkic merchants, leading to the Islamization of crucial regions such as Xinjiang and the Tarim Basin.

Scientific and Technological Transfers via the Silk Road:

- Papermaking, an ingenious invention from China, spread to the Islamic world by the 8th century, eventually reaching Europe via Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) by the 12th century.

- Gunpowder and compass technology, both originally developed in China, revolutionized warfare and navigation in the Western world.

- Advanced mathematical and astronomical knowledge from India (including the pivotal concept of zero) and Persia (like Alhazen’s optics) reached Europe through the contributions of Islamic scholars.

Artistic Syncretism along the Silk Road:

- Gandharan art (found in modern Pakistan/Afghanistan) beautifully merged Greek, Roman, and Buddhist styles, resulting in some of the earliest human depictions of the Buddha.

- Persian miniatures and Chinese landscape painting mutually influenced each other, while Central Asian textiles showcased intricate motifs drawn from a multitude of cultures.

The Decline and Transformation of the Silk Road: The Rise of Maritime Trade

By the 15th century, the Silk Road’s prominence in global trade began to decline, marking a significant shift in its long history. Several key factors contributed to this transformation:

- 1. The Rise of Maritime Routes: Bold European explorers, including Vasco da Gama (1498) and Christopher Columbus (1492), actively sought direct sea passages to Asia, effectively bypassing the traditional overland trade routes.

- The Ottoman Empire’s conquest of Constantinople (1453) severely disrupted existing land-based trade, making sea travel an increasingly attractive and viable alternative.

- 2. Political Fragmentation and Instability: The eventual collapse of the mighty Mongol Empire ushered in a period of widespread instability across Central Asia. This era was plagued by warlord conflicts and rampant banditry, rendering travel along the Silk Road exceedingly dangerous.

- China’s Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) adopted more isolationist policies, significantly reducing the nation's engagement with overland trade networks.

- 3. Transformative Technological Advancements: Remarkable improvements in shipbuilding (like caravels and lateen sails) and sophisticated navigation techniques (such as the compass and astrolabe) made long ocean voyages considerably faster and more economically efficient.

Despite its reduced activity, the legacy of the Silk Road continued to thrive in cultural memory, extensive historical records, and the genetic and linguistic imprints left on the diverse populations it once connected.

Modern Revival: China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the New Silk Road

In the 21st century, the spirit of the ancient Silk Road is experiencing a profound revival through China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013, this monumental project aims to reconnect continents through extensive infrastructure development, strategic trade agreements, and renewed cultural exchanges. The comprehensive BRI encompasses several key components:

- The Silk Road Economic Belt: This component establishes a vast network of railways, highways, and pipelines, directly linking China with Central Asia, Russia, and Europe.

- The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: Focused on ocean connectivity, this involves significant port investments across Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

- Digital and Financial Connectivity: This aspect expands critical digital infrastructure, including 5G networks, e-commerce platforms, and cross-border payment systems.

While the BRI has indeed drawn criticism concerning debt sustainability, environmental repercussions, and geopolitical implications, it undeniably stands as a powerful modern reinterpretation of the enduring Silk Road’s legacy. It continues to foster economic integration and cultural dialogue on a truly global scale.

Conclusion: In summary, the Silk Road stands as a monumental chapter in human history, far surpassing its role as a simple trade route. From its origins during the Han Dynasty in China to the unifying influence of the Mongol Empire, and through its eventual transformation, it profoundly shaped civilizations. This ancient network fostered an unparalleled exchange of goods, technologies, religions, and ideas, creating a tapestry of interconnected cultures across Eurasia. Today, China's ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) echoes this historical spirit, striving once again to build bridges and enhance global connectivity. The Silk Road's legacy reminds us of the power of interaction and the enduring human desire to connect, learn, and trade across vast distances, truly cementing its place as a cornerstone of global history and future aspirations.