The Silk Road: How Ancient Trade Routes Shaped the Modern World

The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road: A Historical Bridge for Global Trade and Culture

Introduction to the Ancient Silk Road

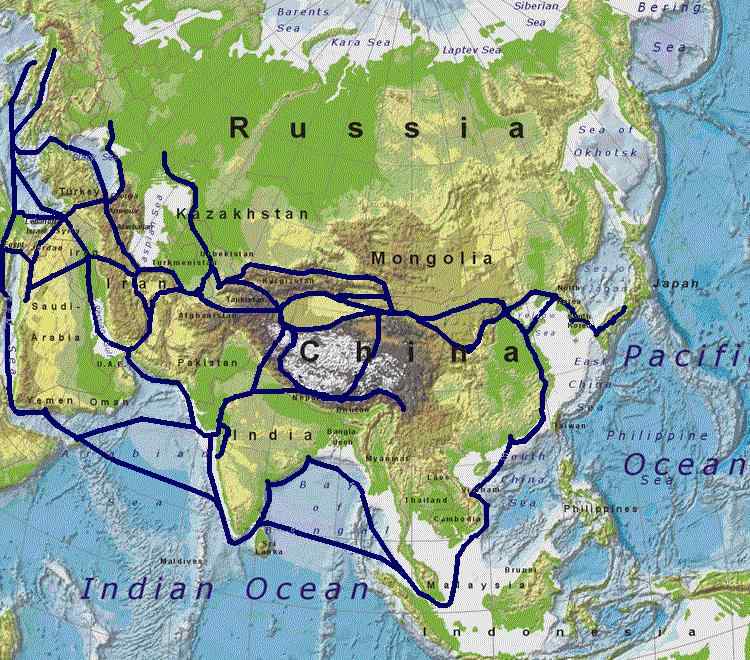

Imagine a network that connected continents, facilitating the exchange of everything from spices to philosophies. For over two millennia, the Silk Road was precisely that – not merely a single path, but an intricate web of ancient trade routes, both land and maritime, stretching over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles). This vast system linked East Asia with the Mediterranean, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. More than just a conduit for silk, its namesake, it served as a dynamic corridor for profound cultural exchange, technological diffusion, and the movement of goods and ideas that fundamentally reshaped civilizations. This article explores the Silk Road's rich historical evolution, its diverse trade, the spread of cultures and innovations, its eventual decline, and its remarkable modern revival through China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Origins and Historical Development of the Silk Road Trade Networks

The foundational elements of the Silk Road were established during China's influential Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Emperor Wu initiated this era by sending his diplomat, Zhang Qian, on crucial missions to Central Asia between 138–126 BCE. While initially focused on diplomatic efforts against the Xiongnu nomads, Zhang Qian's expeditions inadvertently forged vital trade links with the Yuezhi people and the powerful Parthian Empire, thereby paving the way for lucrative Chinese silk exports. Early trade was significantly driven by China’s high demand for Ferghana horses, renowned for their superior strength and endurance. Conversely, regions in Central Asia and the West eagerly sought Chinese silk, a luxurious commodity so precious that it sometimes functioned as a form of currency.

By the 1st century CE, these burgeoning trade networks had expanded significantly, coalescing into three primary routes:

1. The Northern Route (via the Eurasian Steppe) – Connecting Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) to the Black Sea, passing through key cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, and the Caspian Sea. This land route facilitated the flow of goods across vast steppes.

2. The Southern Route (via the Tarim Basin) – Linking China to Persia and the Indian subcontinent, bravely crossing the challenging Taklamakan Desert and reaching important hubs like Kashgar. This was crucial for connecting major civilizations.

3. The Maritime Silk Road – Extending from vital Chinese ports (e.g., Quanzhou, Guangzhou) to Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa. This sea route enabled large-scale trade of bulk goods and further expanded global reach.

Several powerful empires played a pivotal role in facilitating and securing these ancient trade routes:

- Kushan Empire (30–375 CE) – Controlled the strategic Khyber Pass and was instrumental in the expansion of Buddhism.

- Parthian and Sassanian Empires (247 BCE–651 CE) – Served as essential intermediaries, connecting trade between the distant Roman Empire and China.

- Roman Empire (27 BCE–476 CE) – Despite Senate bans aimed at preserving silver reserves, eagerly imported silk, highlighting its immense value.

However, trade along the Silk Road was fraught with danger. Merchants frequently encountered banditry, extreme weather conditions, and political instability. This necessitated travel in armed caravans or reliance on the expertise of Sogdian merchants, who effectively dominated Silk Road trade from the 4th to 8th centuries CE, showcasing remarkable resilience and strategic organization.

Beyond Silk: A Diverse Exchange of Goods and Innovations Along the Trade Routes

While silk undoubtedly remained the most iconic and valuable export, the Silk Road facilitated the movement of a vast array of other essential commodities and luxury goods across continents. This extensive trade network supported diverse economies:

| From East Asia | From Central Asia | From the West (Europe, Middle East, Africa) |

|---|---|---|

| Silk, tea, porcelain | Textiles, carpets, lapis lazuli | Wool, linen, glassware |

| Gunpowder, paper | Horses, camels, fruits (melons, grapes) | Gold, silver, olive oil |

| Jade, iron, lacquerware | Slaves, furs, amber | Wine, coral, ivory |

| Spices (pepper, cinnamon) | Medicinal herbs (rhubarb) | Precious stones (emeralds, sapphires) |

Beyond these prominent items, everyday goods such as salt, sugar, and grains also regularly traveled along the routes, directly sustaining local economies and communities. The spice trade was particularly profitable, with commodities like black pepper from India becoming a crucial staple in Roman cuisine. Furthermore, revolutionary technological transfers occurred; Chinese paper (invented in 105 CE) and gunpowder (9th century) later profoundly transformed European warfare, communication, and overall societal development, showcasing the enduring impact of these ancient trade networks.

Cultural and Technological Diffusion: The Silk Road's Global Impact

Beyond the exchange of goods, the Silk Road functioned as a profound cradle of cultural syncretism and a primary conduit for knowledge transfer. It facilitated the widespread dissemination of religions, artistic expressions, scientific advancements, and linguistic practices across vast continents, fostering unprecedented East-West connectivity:

1. Religious Exchange

- Buddhism, originating in India, significantly expanded its reach into China through the Tarim Basin, deeply influencing Chinese art (exemplified by the remarkable Dunhuang caves) and philosophical thought.

- Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism also spread eastward, establishing thriving communities, particularly evident in Tang Dynasty China (618–907 CE).

- Islam expanded effectively via Arab and Persian traders, leading to the widespread Islamization of Central Asia by the 10th century.

- Other belief systems like Zoroastrianism and Judaism similarly found new adherents and established footholds along these influential trade routes.

2. Artistic Fusion

- The Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara (1st–5th centuries CE) stands as a testament to cultural hybridization, blending distinct Hellenistic and Buddhist artistic styles, famously depicting Buddha with Greek features.

- Mutual influences were also observed between Persian miniatures and Chinese landscape painting, enriching both traditions.

3. Scientific and Technological Transfers

- The critical innovation of papermaking, originating in China, reached the Islamic world by the 8th century, and subsequently made its way to Europe via Al-Andalus (Spain), revolutionizing communication.

- Advanced mathematics, including Indian numerals and algebra, spread westward, profoundly influencing later Arab scholarship.

- Medical knowledge also flowed freely, with ancient Greek and Indian medical texts (such as Ayurveda) being translated into Arabic and Chinese, contributing to global medical understanding.

4. Linguistic Exchange

- Sogdian, an Iranian language, served as the primary lingua franca of the Silk Road until the 9th century, when Arabic and Persian languages gained dominance.

- Languages like Uyghur, Turkic, and Chinese also played crucial roles in facilitating cross-cultural communication and understanding among diverse trading communities.

The Decline of the Ancient Silk Road Trade Networks

The golden age of the historical Silk Road began to wane significantly by the 14th–15th centuries, influenced by several critical factors that reshaped global trade:

1. Rise of Maritime Trade Routes – European explorers, most notably Vasco da Gama in 1498, successfully established direct sea routes to Asia. These new maritime paths offered a more efficient and often safer alternative for transporting large volumes of goods, effectively bypassing the traditional overland trade routes.

2. Collapse of the Mongol Empire (1368) – The fragmentation of the once-unified Mongol Empire led to increased regional instability, heightened banditry, and the proliferation of burdensome tolls, making overland journeys far more perilous and costly.

3. Ottoman Control (1453) – The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire further disrupted established overland trade routes, creating significant barriers and increasing the expenses associated with East-West commerce.

4. Black Death (1347–1351) – The devastating plague, which spread rapidly along the Silk Road caravans, severely decimated populations and economies across Eurasia, leading to a drastic reduction in trade and overall activity.

Despite this decline, the profound legacy of the Silk Road endured, deeply embedding itself in cultural memory, evolving trade practices, and historical diplomatic ties, proving its lasting impact on global interconnectedness.

The Modern Silk Road: China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Global Connectivity

In a significant effort to revive the spirit of ancient trade routes and foster renewed global connectivity, China launched its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. This monumental $1 trillion infrastructure project aims to establish extensive links across continents through diverse networks:

- Land Corridors: Major land-based connections such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Trans-Siberian Railway are being developed to facilitate efficient overland trade and transport.

- Maritime Routes: The initiative includes the development of crucial ports globally, including Gwadar (Pakistan), Hambantota (Sri Lanka), and Piraeus (Greece), expanding vital maritime trade pathways.

- Digital and Energy Networks: Beyond physical infrastructure, the BRI also encompasses advancements in digital connectivity (e.g., 5G expansion) and energy infrastructure (e.g., oil pipelines), broadening its scope of influence.

While the BRI promises enhanced East-West connectivity and economic development, it also faces notable Criticisms & Challenges:

- Debt-trap diplomacy: Concerns have been raised that some participating nations, like Sri Lanka and Zambia, may struggle with the repayment of large BRI loans, potentially leading to debt distress.

- Geopolitical tensions: Countries, particularly the U.S. and EU, often perceive the BRI as a strategic tool for Chinese economic dominance and geopolitical influence.

- Environmental concerns: Many projects within the initiative raise significant environmental concerns, posing risks of ecological damage in sensitive regions.

Despite these challenges, the Belt and Road Initiative fundamentally reflects the enduring principle of the ancient Silk Road: that connectivity is a powerful and necessary driver of economic growth and shared prosperity in an interconnected world.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy and Future of Global Connectivity

The Silk Road was far more than a mere collection of ancient trade routes; it was, in essence, the world’s first engine of globalization. It masterfully fostered deep economic interdependence, facilitated rich cultural hybridization, and spurred monumental technological progress across diverse civilizations. Even after its decline, its profound impact was not erased. Instead, its enduring legacy continues to shape modern trade, influence international diplomacy, and find resonance in ambitious projects like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As the contemporary world navigates the complexities and challenges of modern globalization, the historical narrative of the Silk Road serves as a powerful reminder: the exchange of goods, ideas, and people has consistently been the bedrock of human advancement and shared prosperity. Today, the critical question is not whether East and West will reconnect, but rather how equitably and sustainably these vital connections will be forged for future generations, learning from the rich tapestry of the past.